Topology – Autumn Semester 2023

Hours: 2 hrs, on Thursdays 15:45-17:30

Room: LVML PC-room HIL H40.8 and AV-room HIL H40.5/7

Lecturers: Philipp Urech, Matthias Vollmer, Fabian Gutscher

SEEBAHNGRABEN

The Seebahngraben is an entrenched segment of the Lake Zurich Left-Bank Railway in the district 4 of Zurich. From 1875 to 1927 the Seebahngraben has been reworked until its final stage as a district splitting gap. The surrounding area has changed a lot since then and is now one of the most popular and dense residential neighborhoods of Zurich. The works of 1875 and 1927 leave deep marks on the present of the Wiedikon and Aussersihl neighborhoods. The covering of the entrenched segment is since then open to discussion and plans to cover the rail line date back to the 1960s. Since 2020, the covering has been included in the municipal master plan (“Richtplan”) of the city of Zurich, in which the site is designated as an “open space with a special recreational function (park)”. Current debates about urban climate, mobility and livability call for overcoming the status quo.

Image above: Lake Zurich Left-Bank Railway was originally built at ground level, as shown on this 1921 photograph at the crossing of Badenerstrasse, then regulated with sliding barriers. Source: BAZ

Three successive stages have led to the situation as we know it today. The first stage was the construction of the rail line, which was completed in 1875 and connected Zürich Main Station to Näfels in the Canton of Glarus. This stage coincided with Switzerland’s second railroad construction period, during which major companies expanded by securing concessions from the federal government with strategic foresight. Concerned about missing the extremely tight concession deadlines or losing the rail project to a rival company, construction was carried out with a haste that is astonishing today. With the exception of the old Ulmberg tunnel, today’s road tunnel, the railroad line was laid on the grown terrain without embankments or cuts.

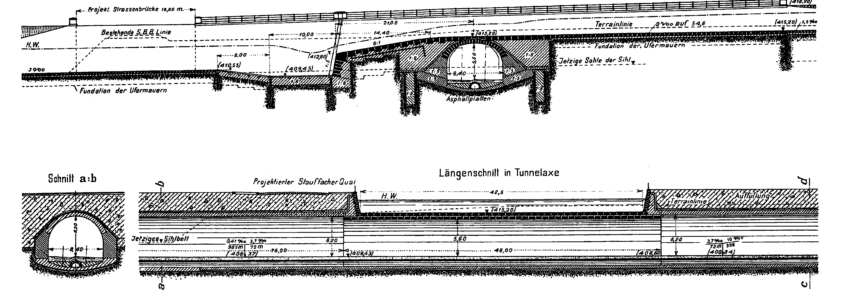

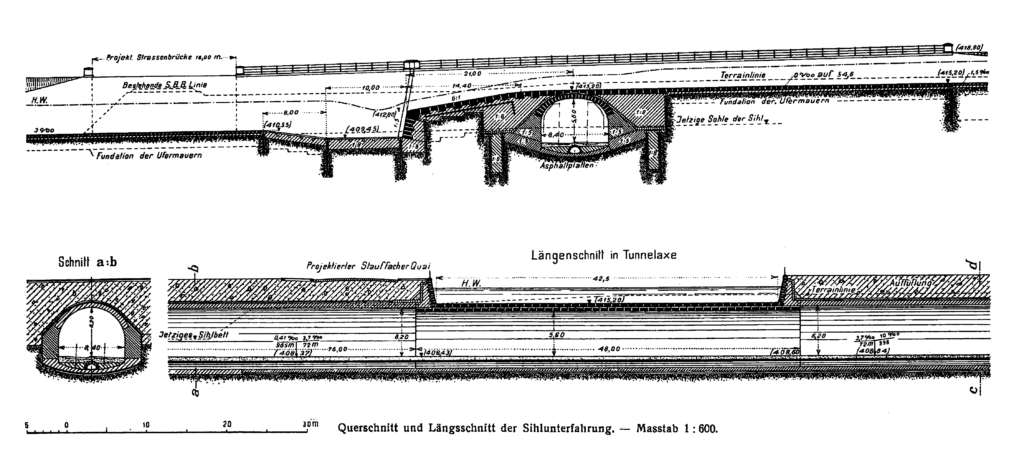

The second stage is the correction of the Sihl river in Wiedikon in the mid-1920s. The correction involved straightening the Sihl river and consolidating the banks, transforming the former island delimited by the river and the Sihl Kanal into the parc landscape and sporting grounds “Sihlhölzli”. Although indirectly connected to the railway, the riverbed transformation was intertwined with the third stage completed in 1927, which involved the entrenching and tunneling of the railway. A step was inserted in the riverbed to build the second Ulmberg tunnel below the Sihl. Lowering the rail line solved traffic congestion in the growing city.

Image above: section of the train tunnel below the Sihl river. Source: Schweizerische Bauzeitung, 25 Februar 1911

APPROACH

The goal of this course is to expand the perception and imagination about the Seebahngraben. The goal is not to produce an exact and feasible proposal to cover the railway trench, but to openly think about new concepts for such a space. For this reason, the course will resort to laser scanning and sound recording to juxtapose existing urban fragments in the form of a three-dimensional collage. Laser scanning can spatially capture buildings, topography, vegetation or even an entire city as a digital artefact. A typical representation of laser scanned data is a point cloud model. Sound on the other hand can capture temporal moments and acoustic atmospheres. Such models carry site-specific and epistemic features, useful to investigate its real-world counterpart. In short, the goal is to tell a fascinating story about a possible future of the Seebahngraben by means of the collected data.

A STUDY OF PLACES

With 40,000 m² to be transformed into an attractive urban area available to people living near the Seebahngraben, it is crucial to understand what qualities could be contributed by the implementation of a rail cover. If “place” is understood as the emergent interaction between people and their environment, what ingredients do people need to value, use, and appropriate it? Various urban places around Zurich carry a status of quality that can be explored in this course, such as:

Place as a meaning — We interact with places beyond their mere materiality. Stories, history, religion have given certain locations a special meaning over time. The meaning can be nested in socio-cultural functions (e.g., Patio de los Naranjos, Sevilla), take the form of an object for memory (e.g., Holocaust Memorial in Berlin by Peter Eisenman and Buro Happold), or be linked to ephemeral events (e.g., The Floating Piers by Christo and Jeanne-Claude).

Place as an atmosphere — Physical elements such as facades, ground, trees or water contribute to the sonic quality of a place. The soundscape can be a very precise tool to analyze the atmosphere as it is an indicator of the social, the environmental, as-well as the infrastructural aspect of a place. Examples are: Singing Ringing Tree by Tonking Liu, 2006 / Harmonic Bridge by Bill Fontana, 2006 / Harmonic Gate by O+A (Bruce Odland und Sam Auinger), 2020, Europaallee Zürich / Zadar Sea Organ by Nikola Bašić, 2005

Place as an artwork — Places can have strong aesthetic expressions, supported by visual relationships such as axes, viewpoints, narrowings or walls. The composition may resort to spatial arrangements such as symmetry to strengthen the sense of order (e.g., garden of Villa Pisani in Stra), void to emphasize boundaries (e.g., Schouwburgplein by West8), or repetitions to indicate direction (e.g., Way of Peace by Dani Karavan).