Digital Design Methods III

Spring Semester 2025

Hours: weekly 2 hrs, on Mondays 15:45-17:30

Room: LVML PC-room HIL H40.8

Lecturer: Philipp Urech

GOAL

This course aims to enhance digital literacy across multiple scales. Participants will develop skills in geometrically digitizing, analyzing, and modeling the physical environment. Photographic survey data will be transformed into three-dimensional point cloud models, integrated with larger LiDAR datasets, and manipulated to generate visual outputs that highlight a site’s aesthetic and topological features. These 3D models serve various purposes, including visual representation, spatial analysis, quantitative assessments, and contextual integration. The sessions will combine theoretical concepts with hands-on data processing. Digital Design Methods III equips students with methodologies applicable to the parallel design studio. A key component of the course evaluation involves effectively incorporating these methods into their design proposals. By the end of the semester, students will be capable of independently applying these techniques in both research and professional practice.

CONTENT

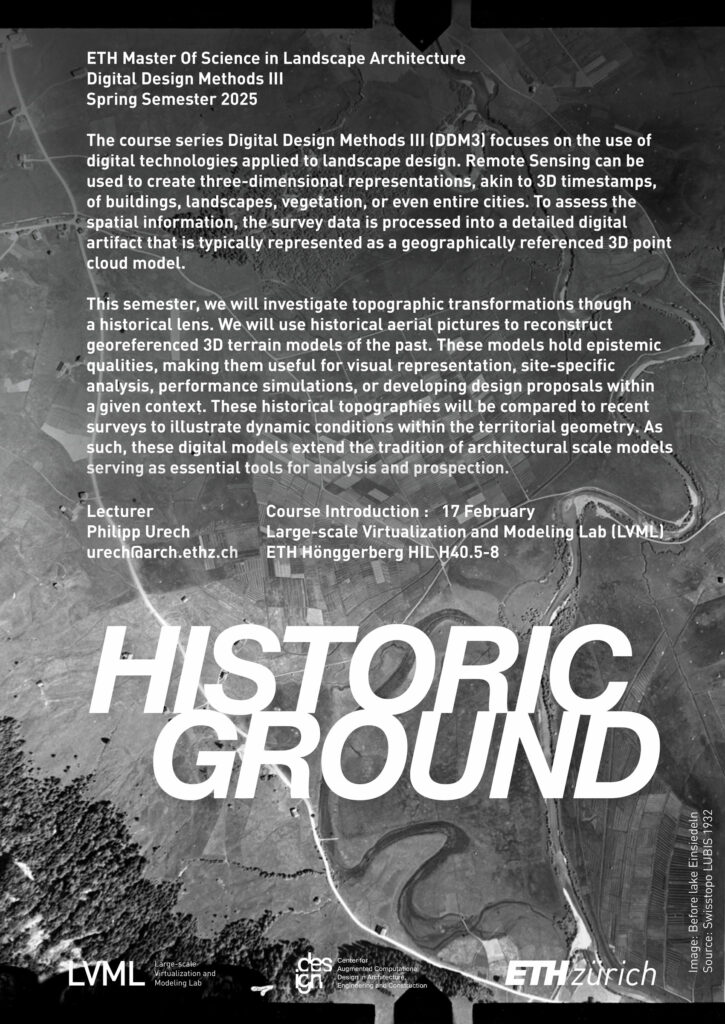

Ground is humanity’s most fundamental infrastructure project. It shapes how people live, work, and structure their societies. Since the Neolithic agricultural revolution, humans have been deeply connected to the land, continuously modifying its surface and soil to support stable production systems and living conditions. Looking ahead, ground remains the infrastructure project of the future. Whether for transportation, agriculture, or energy, infrastructure development is inherently tied to an understanding of topography and soil. The relationship between human activity and landforming is not incidental but essential—without considering the land’s characteristics, modern systems, from food production to urbanization, would be unsustainable. To manage the land effectively, societies have developed various topographic techniques to regulate water flow, nutrient distribution, and biological cycles. Over time, these practices have shaped cultural landscapes through the continuous transformation of the terrain. However, technological advancements between the Industrial Revolution and the Third Agricultural “Green” Revolution have fundamentally altered human interaction with the ground. The mechanization of land management has allowed for systematic terrain optimization with minimal effort. Yet, this efficiency has come at a cost—intensive agriculture and built surfaces have smoothed and standardized landscapes, creating unintended consequences. Straightened terrain accelerates water runoff, causing rain to rapidly form streams and trigger floods, rather than being retained in depressions, infiltrating the soil, or draining at a slower pace. With climate change bringing longer dry periods and more intense rainfall, landscapes must become more resilient, integrating intricate drainage patterns that slow and retain runoff to mitigate environmental risks.

Although systematic and fraught with consequences, topographic smoothing by human activity is unnoticed and underestimated. These transformations generally only affect the surface, altering the topsoil from a few centimeters to a few meters deep. Only the most sophisticated remote sensing techniques, such as terrestrial and aerial laser scanning, can visually reveal how the soil has been artificially manipulated. This course explores the role of large-scale micro-topographic modifications. It highlights the importance of surface structures, such as terraces, berms and retention basins, in slowing the movement of water and promoting infiltration, even during prolonged rainfall events. The course highlights the importance of integrating these elements into urban planning to reduce flood risk and improve water quality. The course presents a micro-macro topographic slicing method, creating a relative elevation model that can be modified to support precise topographic design. A shift from smoothened landscapes to more complex topographies associated with natural hydrological processes would contribute to better manage stormwater, reducing the risk of flooding and improving the overall water cycle.