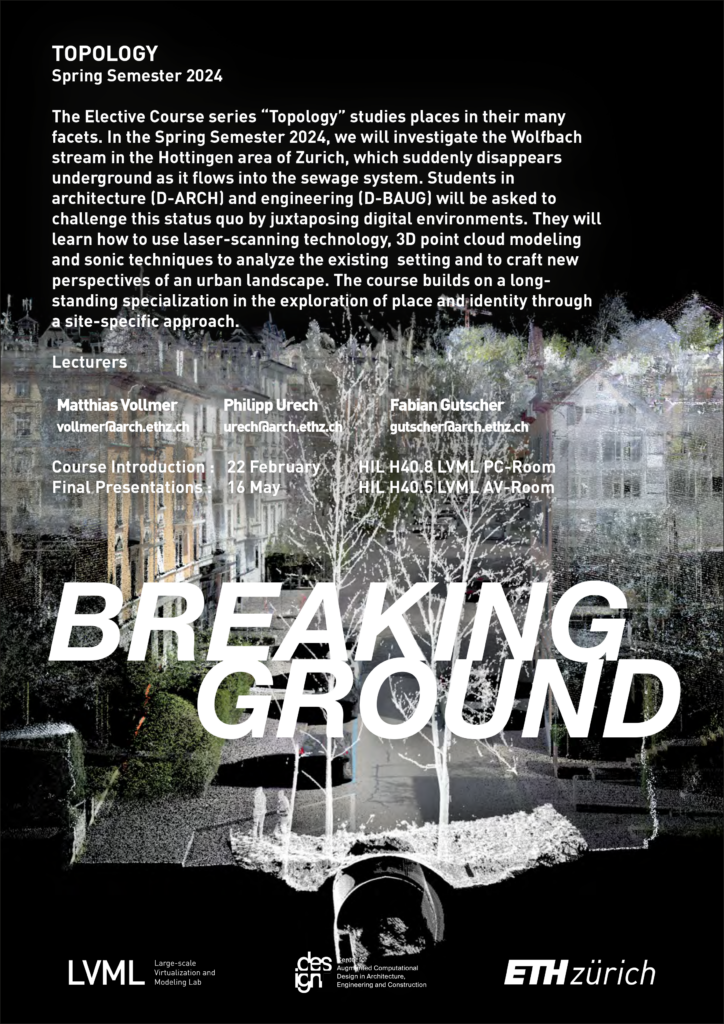

Topology – Spring Semester 2024

Hours: 2 hrs, on Thursdays 15:45-17:30

Room: LVML PC-room HIL H40.8 and AV-room HIL H40.5/7

Lecturers: Matthias Vollmer, Fabian Gutscher and Philipp Urech

Summary of Students work:

WOLFBACH

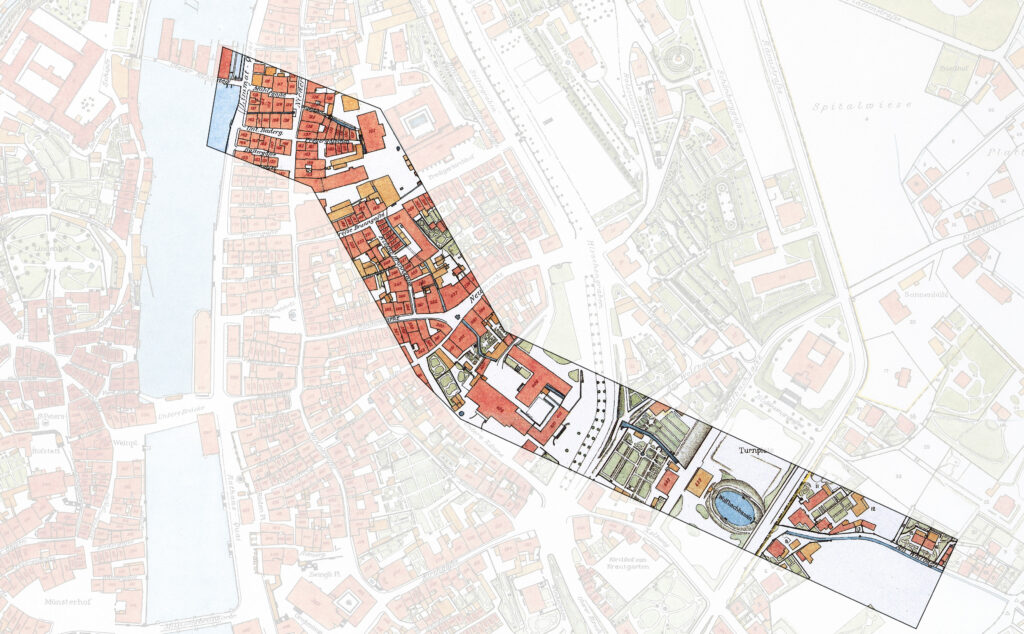

Maps from the 1850s show that approximately 160 kilometers of open streams flowed through the city of Zurich. Until the 1860s, the Wolfbach ran as an open stream through Hottingen in the direction of the current extension of the Kunsthaus before traversing the grounds of the Barfüsserkloster monastery. However, many of these streams were seen as an obstacle to the development of the city as well as a threat to urban health and hygiene. With the expansion of the settlement areas, watercourses were used for draining sewage water and disposing of waste, which resulted in unpleasant odors and sight within the city borders and consequently led to the covering of many streams. The lower segment of the Wolfbach was culverted in 1870. The resulting Wolfbachkanal still exists today and is one of the oldest canals in the city.

Image above: detail of the 1865 map of Zurich, showing the open stream Wolfbach. After passing through Hottingen, the stream flows through the Wolfbachbassin, the Franciscan friary Barfüsserkloster and the Niederdorf before merging into the Limmat. Source: BAZ “C249_5”

In 1926, the city of Zurich began to treat wastewater with the opening of the first sewage treatment plant. In the following decades, the watercourses were gradually cleared from unwanted impurities while remaining buried. In 1980, there were only around 80 kilometers of open watercourses left in the city of Zurich – most of them in wooded areas. What remained were numerous street names that refer to the open streams of the past: Bachtobelstrasse, Lindenbachstrasse, Hegibachstrasse and others. To date, the municipality has developed a new concept for watercourses in the city and has carried out around 50 projects to open up or renaturalize streams and thus uncovered around 16 kilometers of watercourses. In this course we want to try out a new method of changing the urban landscape and return the Wolfbach to daylight!

Image above: Wolfbach in Hottingen, before dissappearing under the Dolderstrasse. Source: Urech 2024

CONTENT

The goal of this course is to expand the perception of urban streams and imagine ways to restore their visual or audible presence in Zurich, to openly think about new concepts for such a place. The course participants choose a sector along the Dolderstrasse and insert within this sector a new place that could emerge by breaking up the existing street to eventually reveal parts of the Wolfbach. For this reason, the course will use an approach of Collage by juxtaposing two places, a “Place of inquiry” (the Dolderstrasse) and a “Place of inspiration” (chosen by the participants). In the process of this digital transposition, a series of questions shall be investigated and answered by the final collage. The questions address interrelated facets that should be considered when juxtaposing the places.

What is a sense of place? Sound: The auditory landscape of a place contributes significantly to its sense of identity. This includes natural sounds such as birdsong or flowing water, as well as human-made sounds like traffic or music. Spatial Structure: The physical layout and arrangement of spaces within a place shape how people interact with and perceive it. This includes elements such as pathways, vegetation, buildings and landmarks that define the spatial organization and flow. Materials: The choice of materials used in the construction and design of a place can significantly impact its character and sense of place. The texture as well as the resonance of different material change the acoustic and visual impression.

What makes water tangible? Physical Presence: The sight, sound, and feel of water in its various forms—whether it’s flowing in a river or gently trickling from a fountain—makes it tangible by engaging our senses. Revitalization: Water’s ability to sustain life and rejuvenate the environment can make it tangible. Revitalizing landscapes through the presence of water, such as restoring or creating urban green spaces with water features, can bring a sense of vitality and connection to the natural world. Restoration: Restoring waterways can make water tangible by reconnecting communities with their natural surroundings and cultural heritage. Efforts to restore rivers, lakes, and coastal areas not only improve water quality but also foster a sense of stewardship and appreciation for the environment.

What are the intensions? Ecology: One intention might be to enhance the ecological sustainability of urban areas by incorporating green spaces, implementing green infrastructure and promoting biodiversity through urban planning and design. Community: Changing the urban landscape with a focus on community can involve creating inclusive public spaces that cater to the needs of diverse populations, fostering social interaction and cohesion among residents. Artwork: Artwork can serve as a means of expressing and reflecting the values, aspirations, and experiences of urban communities, sparking dialogue and fostering a sense of connection among residents.

What are the effects / consequences? Sensory Atmosphere: Transformations in the urban landscape, such as the introduction of green spaces, can influence the visual and sensory atmosphere of the city, shaping its identity and character. Physical Health: Walkability, access to green spaces, and active transportation options can have positive effects on public health, promoting physical activity, reducing sedentary lifestyles, and mitigating chronic diseases. Mental Health: Enhancements to the urban landscape, such as the creation of vibrant public spaces and the preservation of cultural heritage, can contribute to residents’ mental well-being by fostering a sense of belonging, social cohesion and cultural identity.